Dr Allan Wardhaugh, Consultant Paediatric Intensivist and Chief Clinical Information Officer at Cardiff & Vale University Health Board reflects on the journey of video consultation in Welsh healthcare.

A good colleague used an interesting metaphor a few years ago when describing the process of trying to change and innovate in the health service. It was about non-Newtonian fluids, with the specific example being ‘Slime’, which was quite popular with kids a few years ago. A quick trip on Google will take you to videos showing how to make your own non-Newtonian fluid using water and cornflour (it’s called Oobleck, apparently). When handled gently, they have low viscosity – they behave and feel like normal fluids: you can run your fingers through them, they will flow, if not like water, certainly like runny honey. The interesting bit comes if you push too hard. If you jump on the surface or hit it with a hammer the fluid behaves like a solid. It resists ‘rapid deformation’. Punching it is like punching concrete. I don’t need to spell the metaphor out.

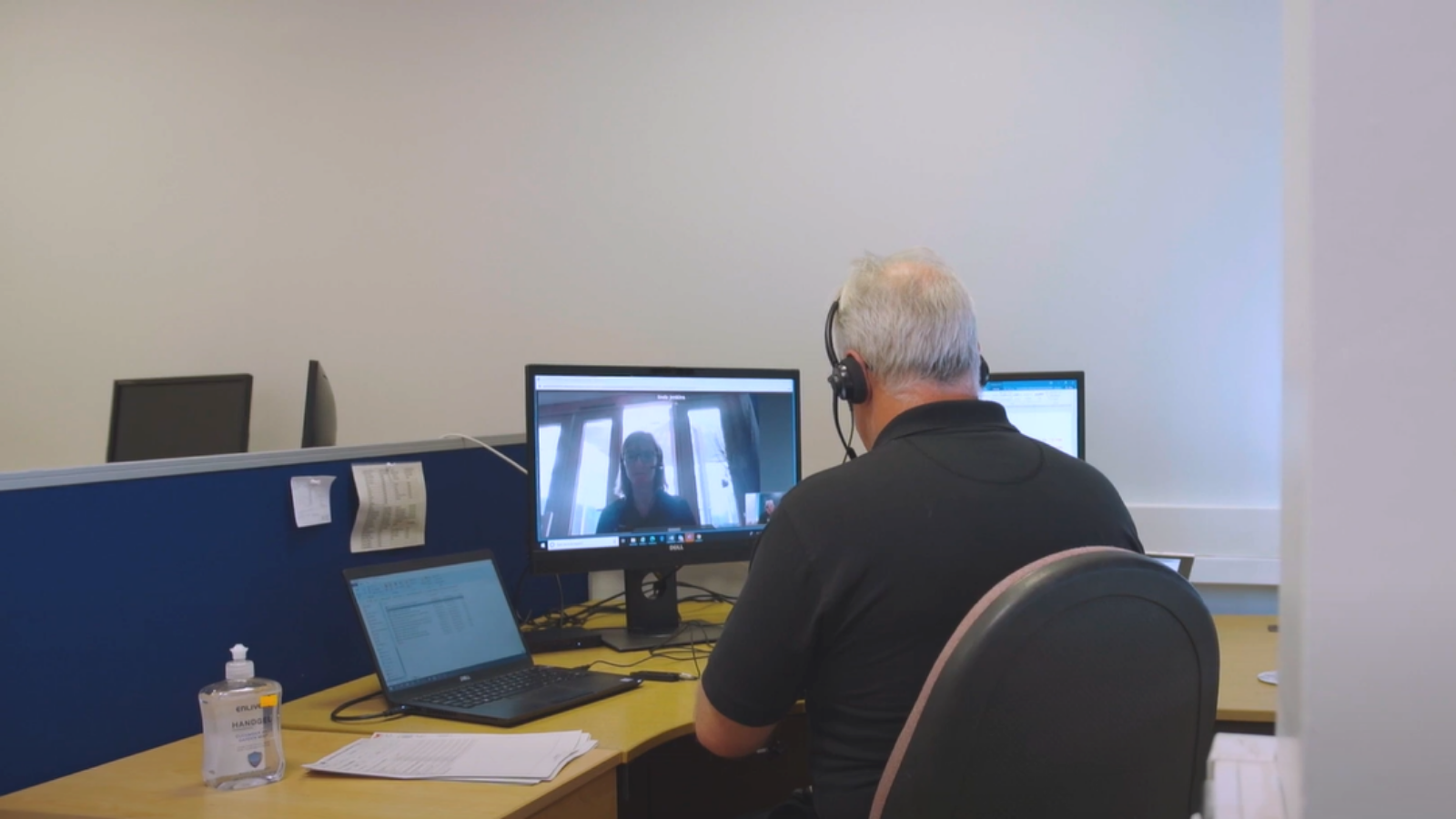

Video consultations (VC) were an early and important initiative when the COVID-19 pandemic started. The concept wasn’t new – many of us have been using VC technology for years via Skype, FaceTime and other applications. Indeed, Skype licenses had been purchased in significant number for use in NHS Wales a few years ago – although without any clear plan or outline of how it would be used – or ‘rolled out’. The advantages in terms of reducing travel time and inconvenience for patients were obvious, but the disadvantages of being unable to make a physical examination and miss the nuances of face-to-face communication were unclear. A few services were ‘exploring’ the use of Skype, but generally these were small-scale and ad hoc. Interestingly, the view among many clinical colleagues (who didn’t use VC at work) was that they couldn’t understand why it wasn’t more widely used. ‘We just need to start using it, we just need to roll it out…’. I’ve learned that the phrase ‘we just need to’ is a flag indicating frustration, but also a lack of understanding of the complexity of introducing apparently simple technology which significantly changes the way we work.

In the first few weeks of the pandemic, the ability to ‘see’ patients remotely became an imperative forced by lockdown. In many cases a telephone might suffice, but there were many clinicians asking for the ability to perform VC – with many taking the decision to start doing this using proprietary technology on their own devices in the absence of an alternative. Conversations about rapid introduction of a VC platform on a ‘Once for Wales’ basis emerged, and Welsh Government started to explore this, quickly procuring Attend Anywhere to provide this capability. Job done. Just roll it out. The future is here. We can close outpatient departments. Target percentages were being discussed. Everyone must use Attend Anywhere. This is when it was important to remember non-Newtonian fluids.

Those of us in the world of Clinical Informatics have been learning over recent years about what works and what doesn’t in implementing digital technology into healthcare. The most prominent report into this remains the so-called ‘Wachter Report’ into the failure to digitalise NHS England despite the billions invested. A key finding was the need to have meaningful clinical engagement to lead the ‘adaptive change’ that flows from a new digital technology – the business change, the ‘new ways of working’. This is an exploratory process, not something that can be described or prescribed in detail from top down. This is closely related to the ‘agile working’ principles developed by Government Digital Services – avoiding the temptation to make everything perfect before the ‘go-live’ but instead accepting ‘good enough’, but then listening to user feedback, evaluating outcomes and iteratively developing the solution.

I look back now on those early days of VC and feel glad that we adopted those principles in taking VC forward. We understood we were undertaking an ‘implementation’, not ‘rolling out’ a product. Welsh Government listened and accepted that while their procured VC platform might cover the needs of most services (‘use cases’ in the informatics lingo), there would be other platforms already in use in particular areas and for very specific use-cases which Attend Anywhere would be unsuited to, or an enforced change-over too burdensome. We didn’t know what they were – but we knew there would be some. So ‘Once for Wales’ (a phrase deceptively simple but often hugely problematic) became about the approach rather than just the product.

The principles of agile methodology, understanding the need for good central co-ordination but enabling locally led (and clinically led) implementation and recognising the strengths and weaknesses of the technology – including the dependencies on the state of each organisation’s infrastructure – were promoted by TEC Cymru. This small NHS Wales initiative hosted in Aneurin Bevan University Health Board had been formed a few years ago to develop an understanding and approach to using ‘Technology Enabled Care’ to improve services for patients and they had supported a successful pilot of Attend Anywhere in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CWTCH project). Their learning was put to effect across the country, but with the help of the emerging network of clinical informatics leads in the local organisations.

The ability to implement locally according to our own service configuration, infrastructure and staff insights has been very positive. In Cardiff and Vale, we devolved implementation activities to divisional teams comprising clinicians, operational managers and members of our technical teams. Those teams met frequently, but for focussed ‘stand-up’ style meetings (albeit virtual), were not overburdened by governance and developed a sense of ownership of the programme. Importantly, we were given the freedom to do this from the top of the organisation – we were trusted to deliver and not encumbered by arbitrary targets or a continual requirement to provide RAG spreadsheets. All of us involved have embraced this way of working and are using it as a template for the future.

The ethos of this programme has been to continuously evaluate and learn. What areas does VC work in? Where does it not work and why? Is it accepted by patients and clinicians? Is it being used in unexpected ways? Will these findings, gathered during a global pandemic, be applicable when we have emerged from it? I’d suggest those findings might make a good follow-up blog, but TEC Cymru have now published two evaluations addressing these questions and more. It is a bit dispiriting to see some of our media trying to stir-up a polarised debate about face-to-face appointments versus virtual. They complement each other. Better maybe to acknowledge our continued efforts to understand where VC fits in to the suite of services we offer our patients.

Welsh Government recently published its National Clinical Framework. It provides a template to develop a ‘Learning Health and Care System’. The acknowledgement implicit in that approach is that we need to accept that we must transform the way we deliver care, but that process is iterative. We can’t know all the impacts of new ways of working – our system isn’t just complicated, it is complex. If we become better at collecting data, continuously collect and analyse outcomes and experiences then learn from those evaluations we will surely be able to improve services more effectively. By engaging the staff who provide the services and the patients receiving them in this process, we all become part of the adaptive change and shape our future health system. This requires a considered, guiding hand to shape and co-ordinate, not a central clunking-fist that will simply inspire non-Newtonian resistance. We’ve demonstrated that approach in the national VC programme – so let’s take those lessons into the system as a whole.

Allan Wardhaugh

Consultant Paediatric Intensivist & Chief Clinical Information Officer

Allan Wardhaugh

Consultant Paediatric Intensivist & Chief Clinical Information Officer